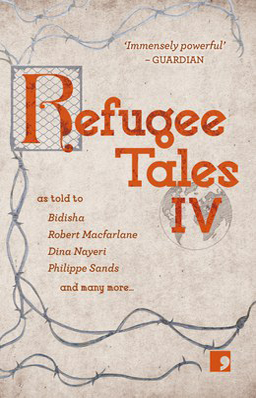

Below is an edited version of the Afterword of ‘Refugee Tales 111’, by David Herd. It powerfully presents the situation in which most of our clients find themselves. Go and buy the book! All profits from the Refugee Tales series go to Gatwick Detainee Welfare Group and Kent Refugee Help.

Refugee Tales, as we reiterate everywhere we go, is “A Walk in Solidarity with Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Detainees”. The purpose of the project is to call attention to the fact, to call out the fact, that the UK is the only country in Europe that detains people indefinitely under immigration rules, and to call for that practice to end. The way the project makes that call is by sharing the stories of people who have experienced detention. The stories are told and heard in the context of the community that forms through walking. When Refugee Tales walked in July 2019, it was for the fifth time.

It was not part of the original plan to walk for five years. That plan was formed by members of the Gatwick Detainees Welfare Group out of a shared frustration that, while the Group’s volunteers had been visiting people held in indefinite detention for twenty years, the general public was barely aware that such a practice was being conducted in their name. Almost everything about detention and its consequences was rendered publicly invisible.

The plan, then, was to share the stories of people who had been held in detention, and to do so as part of an extended public walk. The idea was shared with groups working with people detained at the Dover Immigration Removal Centre – Kent Refugee Help and Samphire – and a route was developed that went from Dover to Crawley (the nearest town to the detention centres at Gatwick Airport) along the North Downs Way. That first walk lasted nine days, the aim being to create, in that act, a kind of spectacle of welcome and in so doing to help trigger the desire for change. Except that as people walked that first year it became clear that the project had no choice but to continue, that for at least two compelling reasons it couldn’t stop.

The first reason was political. If the project was serious in its call for an end to indefinite detention, then it was clear that call would have to be made louder and for longer if it was to be widely heard. Refugee Tales was adding its voices to those of the many organizations and individuals who had been fighting for an end to indefinite detention for many years, and though the calls were intensifying inside and outside parliament it was apparent to everyone involved that more work had to be done. What was also clear, however, was that as people who had experienced detention walked with people who hadn’t, so in that process a community formed. For everybody involved, albeit for different reasons and from different viewpoints, the walk constituted a space outside the hostile environment that, as home secretary, Theresa May had first set out to inflict on the UK in 2012.

For each of the following three years the project walked to Westminster: from Canterbury in 2016, from Runnymede in 2017, and from St Albans via the East End of London in 2018. Everywhere it stopped it shared stories of people who had experienced detention with the general public, the venue frequently doubling as the space in which the project would collectively spend the night. At each evening event the facts of detention would be reiterated and the audience would be called on to help communicate the urgency of the need for change, in particular to build pressure on a government in blatant breach of human rights. Then, during the walking day, the stories from the night before gave rise to further stories. In 2017, for instance, the walk having started at the site of the sealing of Magna Carta, a series of speakers considered the question of “due process”. In 2018, talks took their lead from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Article 9 of the Declaration could not be clearer, “Nobody shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention, or exile”, a basic provision of human protection with which the UK government is in conflict. This year the Refugee Tales route ran from Brighton to Hastings, walking the coastal border.

What is crucial to report, against the background of all this movement, is that there are people who first walked with Refugee Tales in 2015 whose situation hasn’t altered: who still can’t work, who are still forced to exist outside the cash economy, who still, at any moment, could find themselves re-detained. In “The Voluntary Returner’s Tale”, told in 2016, Caroline Bergvall detailed the effect of “slow violence”– a form of violence the hostile environment was constructed to perfect.

In an interview with the Daily Telegraph in 2012, Theresa May announced the intention to use the Immigration Act of 2014 to create a “really hostile environment for illegal migration”. The 2016 Immigration Act further intensified that hostility, with its root-and-branch foreclosure on anything like a liveable life. At the same time, however, as official hostility to those seeking asylum has intensified, so also the Home Office’s practices have become much more widely known and discussed in the media, though this can hardly yet be said to have altered Home Office behaviour. And seven years on from Theresa May’s announcement of the government’s intention we are still coming to terms with what the hostile environment has brought into effect.

The hostile environment, as the 2016 Immigration Act confirmed, is a sustained, systematic and brutal assault on every aspect of the life of the geopolitically vulnerable person. Denied the right to work for as long as their case is unresolved, which will frequently be for years and can easily be for well over a decade, a person seeking asylum finds their every movement compromised and controlled. As has been observed by Refugee Tales before, but which needs constant reiteration, such support as is afforded a person in that circumstance (at the subsistence level of £5.39 per day) is paid not in cash or into a bank account (which since the 2016 Immigration Act it has been illegal for a person seeking asylum to hold), but as a voucher in the form of a top-up card that can only be spent on designated products at designated shops. This renders even the act of securing basic provisions a hostile process since the voucher – like a badge – has to be displayed at the point of transaction. It also subjects human movement itself to the process of hostility, since public transport is not listed as an item on which the voucher might be spent. One effect of this is that a person will spend endless hours walking, either to secure basic provisions, or to sign at a Home Office Reporting Centre, or because in the absence of work there is precious little else to do.

At any moment the individual might (if they are in the unusually fortunate position of occupying Home Office accommodation) be relocated to another part of the country. The government’s word for this is “dispersal”. People frequently find themselves “dispersed” – a process which has the

consequence of breaking up such community as they might manage to form. But at any given moment (since the process is arbitrary) a person can also be detained or re-detained. It is in this sense that the hostile environment has to be understood. Not simply (though this would be bad enough) as a set of bureaucratic procedures in which by accident or design an individual’s future can get lost. But as a total space of existence in which the individual’s personhood is shaped by hostility.

As much, then, as the policies that constitute this assault on the politically vulnerable person are now known, still we are in the process of understanding their implications and political reach. Like any newly emerging normal, it takes time to realize what is at stake. As we do so, many have drawn on the work of Hannah Arendt. The importance of Arendt (who fled Germany in 1933, and German-occupied France for the USA in 1941) is that more clearly than any writer since the Second World War, she documented how the person who seeks asylum can find themselves abandoned between nation states. Her discussion of statelessness and rights in Origins of Totalitarianism (1950) remains unerringly accurate in its description of the vulnerability into which a stateless person can slip.

What has become apparent, however, in the past five years, as right-wing narratives of nation have gained sway in parts of Europe and America, is that we have to heed Arendt’s warnings more closely and more urgently than we would have wanted to think. Thus, one thing Arendt was very careful to observe was how administrative hostility could give way to, or could prepare the ground for, further large-scale assaults on personhood. As she put it, “the methods by which individuals are adapted to these conditions, are transparent and logical”. Thus the insanity of the historical developments she was seeking to understand in Origins of Totalitarianism had its root, as she understood it, in administrative hostility, in the “historically and politically intelligible preparation of living corpses”.

Arendt’s history of totalitarianism was written in the form of a warning. Her aim was not to argue that one historical development follows straightforwardly or in any simple fashion from another, but that there are tendencies in politics by which we have to be alarmed. When recently, under the Salvini Decree, the Italian government bulldozed the Castelnuovo di Porto refugee reception centre just outside Rome, evicting hundreds of refugees, the authorities were acting on grounds Hannah Arendt would recognize. The people concerned had been rendered so politically vulnerable as to make them subject, eventually, to state-orchestrated violence. Understood historically, it is just such ground that UK policy-makers began to prepare when they instigated the hostile environment. The intention was to produce the conditions through which personhood itself could barely be sustained. The longer that environment exists the more we understand its implications. To detain a person indefinitely is to so fundamentally breach their human rights as to render them outside the provision of any ethical framework. In order to detain indefinitely, in other words, the state must already have taken the decision that this is a person to whom rights don’t apply. From which it follows that their personhood does not require respect. From which it follows that one can develop a comprehensively hostile space.

It is the prospect of such arbitrary detention that instils the fear that shapes a person’s relation to their everyday life. The number of people actually detained has remained stubbornly high through the past five years. The Home Office points to incremental reductions as a sign of improvement, but in the year ending in December 2018, 24,748 people were detained indefinitely in the UK. Among the constants, in fact, of the past five years are the statistics around detention. Thus, of all those detained in that time, somewhere between 50 and 55 per cent were released back “into the

community”. What “community” means, in this context, is the situation described above, without work and where every movement is negatively managed. Still, though, since the Home Office’s justification for indefinite detention is that it is preparatory to removal, then the fact that in the year ending December 2018, 55 per cent of those detained were returned to the community shows that either detention is ineffective even in its own terms, or, alternatively, that its function is brutally symbolic.

Periods of detention continue to vary. Sometimes it will be days, sometimes weeks, but it can be for months and years. The longest Refugee Tales has known of a person to be detained indefinitely in the UK is nine years. At last count, and counting, the longest current period of detention was 744 days. In the year ending June 2018, ten people died while in detention and 159 people attempted suicide. To end indefinite detention would not be to end the hostile environment. It would, however, be to dismantle a fundamental aspect of its architecture.

During the period that Refugee Tales has walked, the international use of detention as a political weapon has become increasingly widespread. The examples are numerous, from the Trump administration’s separating of children and families in detention centres at the US–Mexican border, to the continued offshoring of detention by the Australian government, to the routine detention of political dissidents in Turkey. One could easily proliferate examples, and in doing so one could dwell on differences between political regimes. What needs to be understood, however, is that for all kinds of regime, detention is an increasingly common default, and that therefore it has become one of the defining issues of our time. Detention is a global practice that increasingly defines geopolitical space. It has to be confronted wherever it is practiced in the national context but also by networks working internationally.

As various organizations have reported, the bail hearing where an individual might be released from detention is not a court of record. This is true, also, of the deportation appeal hearing. While the judge will issue a determination, in which some account of the proceedings is given, there is no full transcript. Consider also the fact that, insofar as the individual does present their story, that story is administratively weaponized against them. If, for instance, having first given an account of their experience in, say, 2003, and then, when called on twelve years later to account for the same experience at a different moment in the process, the person seeking asylum departs from their original telling in any way, then that divergence will be used to discredit the whole case. Or consider the fact that, as the narrator of “The Volunteer’s Tale” reported during this year’s walk, one form of the asylum interview consists of an official asking approximately one hundred questions, and then, when they have finished, immediately asking the same one hundred questions again, seeking small deviations. These processes do not simply silence, they turn the story against itself.

What this surely shows is that the story itself is powerful, when it is told and heard in its entirety it will have an altering effect. To tell and to hear a story, in other words, is to establish an intimate connection, a connection the hostile environment sets out explicitly to break.

Among the most brutal effects of the hostile environment is precisely how, in so many cases, it does not allow a person’s story to change. Simply put, in the five years that the Refugee Tales project has been in existence, the majority of those in the project who have experienced detention have seen no

change in their post-detention life. Still they can’t work. Still they are compelled to live outside a cash economy. Still each time they report their presence to the home office they face the prospect that they might be re-detained.

The hostile environment is sustained by a series of settings in which those in authority feel no obligation to listen. As the 2019 walk was told, so concerned were the authorities to establish whether or not one detainee had been fingerprinted in Italy, that they did not register the fact that he had been tortured in Libya and Sudan. It was only, as he says, when he was visited by a representative of the organization Medical Justice that somebody actually stopped to listen.

On the particular question of indefinite detention there is no doubt that political progress has been made. In 2015, the All Party Parliamentary Groups on Refugees and Migration reported on the Use of Immigration Detention in the United Kingdom and concluded that, “There should be a time limit of twenty-eight days on the length of time anyone can be held in immigration detention”. In 2017 the British Medical Association and the Bar Council, reporting independently from their separate professional viewpoints, echoed the urgent need for such a limit. In 2018, making that need graphic, BBC’s Panorama programme documented the treatment of people detained at the Brook House Immigration Removal Centre. In March of this year, the Home Affairs Committee report on immigration detention found that “Home Office policies … are regularly applied in such a way that the most vulnerable detainees, including victims of torture, are not being afforded the necessary protection” and echoed previous reports in calling directly for indefinite detention to end. All opposition parties committed to ending indefinite detention in their 2017 manifestos, while public support for legislative change has recently been communicated by various government MPs. The political argument, in other words, for an end to indefinite detention has unquestionably been won. The task now is to effect the change of law that reflects this new political reality.

Five years after the project began planning its first public walk, Refugee Tales continues to call out the fact that the UK is still the only country in Europe that detains people indefinitely under immigration rules. With each year that the project has walked, it has become increasingly clear just how systematic are the processes of the hostile environment, just how brutal is that environment’s assault on the fundamentally vulnerable person. It is the power to detain indefinitely that underwrites the totality of that assault. Refugee Tales walks in solidarity with all those who call for that brutal practice to end.